Policymaking and hunting have a few things in common. Like hunters, policymakers are often tracking moving targets. Think of rising inflation, dwindling economic output, or volatile foreign exchange rate. And just as a hunter’s shot must be fired precisely to make a kill, so must a policymaker’s intervention be focused appropriately to succeed. There is just one difference between the two: if a hunter misses his shot, he loses only his bullet. For policymakers, missed shots are often more calamitous.

To exemplify such a calamitous policy, look no further than one of the signature agricultural policies of the previous Nigerian government. In August 2019, the government partially closed the country's land borders and halted all trade via land borders in October 2019. This policy, which remained in effect until December 2020, was aimed at stimulating the country’s food production (See Tweet).

Former President Muhammadu Buhari Justified Border Closure via tweets

Former President Muhammadu Buhari Justified Border Closure via tweets

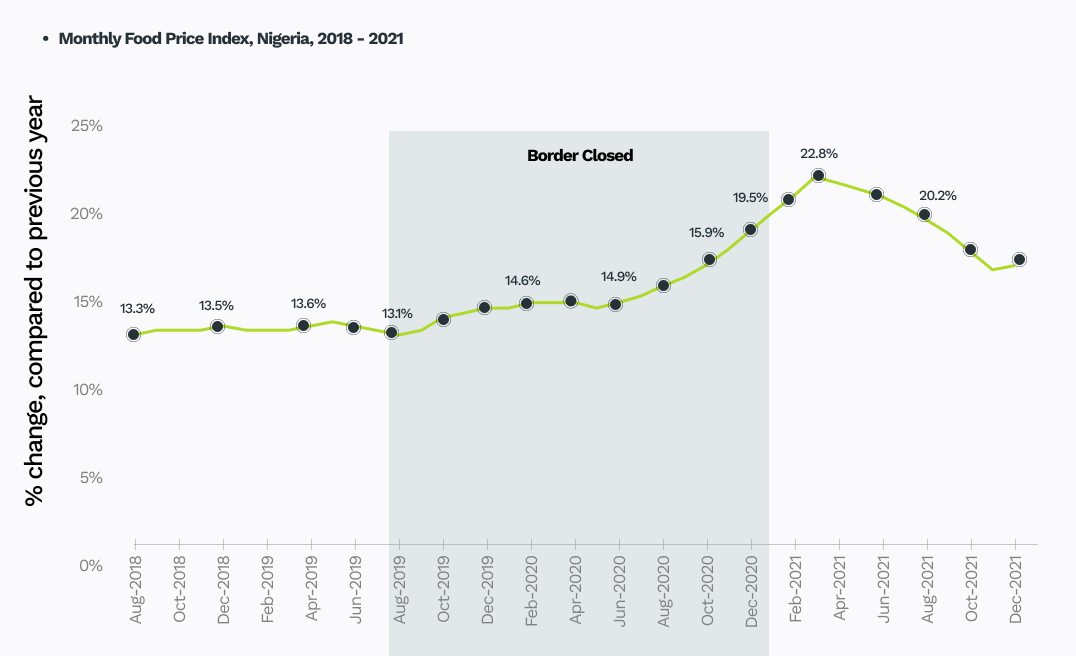

While the policy was well-intentioned, what followed was certainly unintended. The border closure was followed by acute shortages of major staple foods and widespread hunger. Food inflation, which was stable in the months prior to the policy, jumped and continued to rise (Figure 1). Only after borders were re-opened did food inflation begin to slow.

Figure 1: Monthly food price index, Nigeria, 2018 - 2021. (Data source: IMF)

Figure 1: Monthly food price index, Nigeria, 2018 - 2021. (Data source: IMF)

Underpinning this policy was a simple but specious idea. The government’s argument was that foreign foods were crowding out locally grown foods in Nigerian markets, and that to boost local food production, imports of foreign foods must be restrained. This idea contradicts conventional wisdom in economics which advises that the practical way to improve your fortunes is to raise your game, not to wipe out your competition.

Economic ideologies aside, the policy also relied on flawed assumptions. The government assumed that shutting the borders would substantially limit food imports, that Nigerians would simply switch to local foods if their preferred foreign varieties became scarce, and that the Nigerian agri-food sector could quickly ramp up domestic food supply to meet increased demand. These assumptions have since proven fallible.

Stay up-to-date!

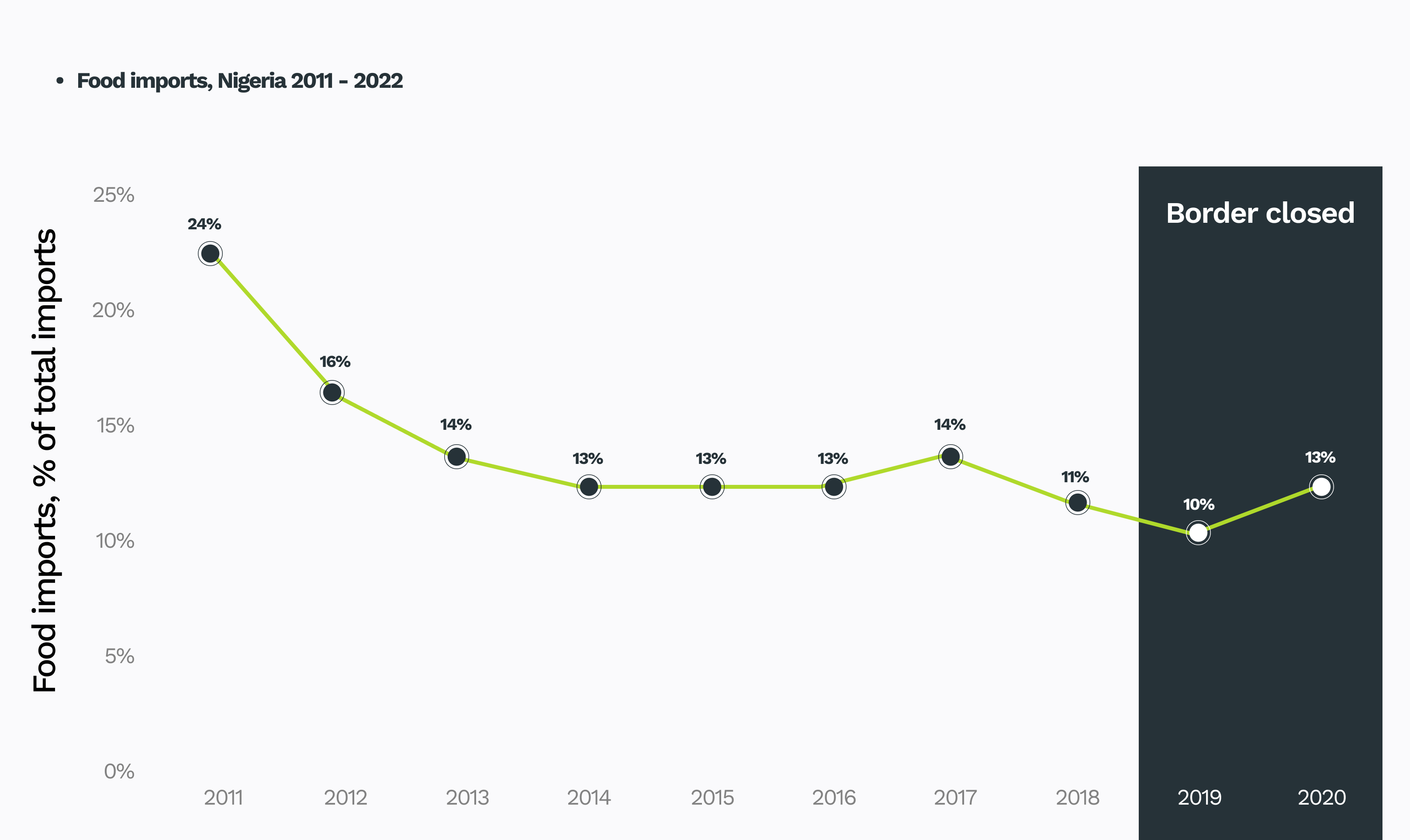

Start with the first one. In the period that the border closure was in effect, there was no notable decline in Nigeria’s food imports. In 2019, food imports were roughly 10 percent of Nigeria’s total imports, slightly lower than the 11 percent recorded in 2018 (Figure 2). But in 2020, when the border closure was in effect for the entire year, food imports as a percentage of total imports increased, reaching 13 percent.

Figure 2: Food imports, Nigeria, 2011 - 2020. (Data source: Observatory of Economic Complexity)

Figure 2: Food imports, Nigeria, 2011 - 2020. (Data source: Observatory of Economic Complexity)

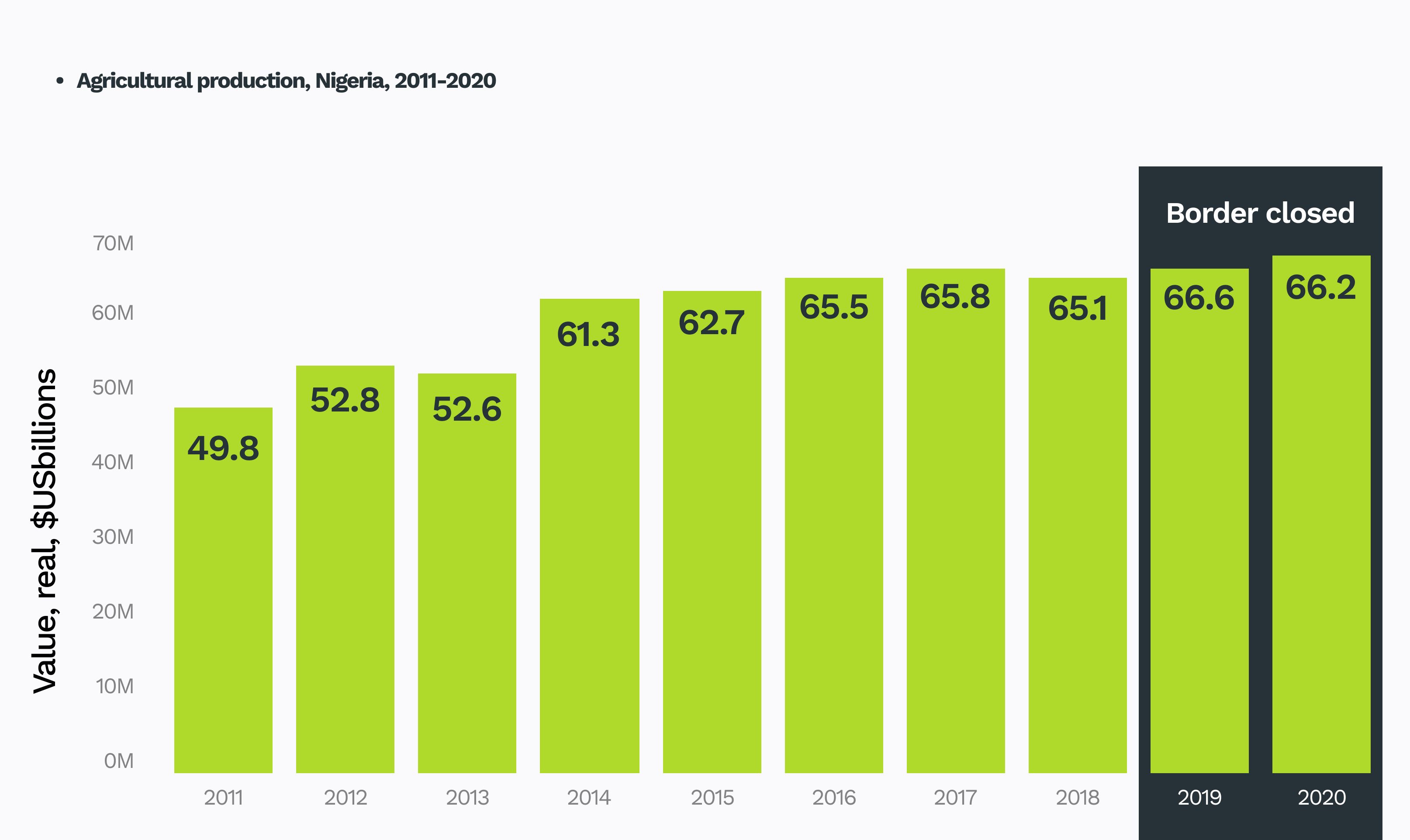

The expected increase in Nigeria’s food production also did not materialise. In 2019 and 2020, the two years affected by the policy, Nigeria’s annual agricultural output was just over US$66billion, about US$1billion above 2018 levels (Figure 3). However, this increase was a continuation of the upward trend in the country’s agricultural outputs since 2011 and cannot plausibly be attributed to the border closure.

Figure 3: Agrictultural production, Nigeria, 2011 - 2020. (Data source: FAOSTAT)

Figure 3: Agrictultural production, Nigeria, 2011 - 2020. (Data source: FAOSTAT)

So, it appears that the policy failed. Despite the embargo on food imports via land borders, food imports neither substantially slowed nor did domestic food output significantly grow.

“But if the policy had no effect on food imports and food supply, how then could it have led to rising food prices?”, one might be inclined to ask. The answer is not far-fetched. Given Nigeria’s porous borders and customs system, the border closure likely made food importation harder but not impossible; food importers simply transferred the added strain imposed on their work to consumers in the form of higher prices. In addition, news of closed borders likely created a narrative of scarcity, causing food markets to panic, and further driving food prices skywards. It is no coincidence that food inflation began to slow after the borders re-opened (Figure 1).

The lesson for policymakers is simple. Agri-food systems involve complex and interconnected dynamics, and government policies are likely to fail if they target distal issues while ignoring proximal problems. If the government’s objective is to stimulate food production, its policies should focus on addressing the immediate value chain gaps that hinder the country’s agri-food sector from being globally competitive.

Shutting borders to boost food production is like a hunter aiming his shotgun at a bird flying in the distant horizon while ignoring a bull foraging nearby. If he hits, he ends up with a bird instead of a bull. If he misses, he ends up with nothing. Either way, a sensible hunter would not abandon an immediate target in favour of an improbable pursuit. Neither should policymakers.