Nigeria's agricultural sector is at a crossroads. Despite contributing almost a quarter of GDP and engaging over 40 million households, the agricultural sector remains incapable of feeding the country’s population. This forces the country to rely on food imports to complement local production. As a result, government priority for the sector, as outlined in the National Agricultural Technology and Innovation Policy (NATIP), focuses on increasing the food supply for domestic consumption while lowering the country’s food imports.

What is NATIP?

NATIP is a 6-year national agricultural policy, incorporating the intervention instruments and implementation strategy, aimed at the sustainable development of the national technological and innovative capacity to fast-track increased productivity, and import substitution, with particular emphasis on the reduction of rice, dairy, meat and fish imports, with increased resilience through digital and climate-smart agriculture, towards promoting agricultural value chains and investments. (Excerpt from the National Agricultural Technology and Innovation Policy (NATIP) 2022-2027)

Meanwhile, over the past 10 years, Nigeria has suffered two economic recessions—in 2016 and 2020—that were largely driven by over-dependence on crude oil exports amidst falling oil prices. Recognizing the need to prevent the recurrence of such downturns, the government also has an interest in diversifying exports through agribusiness. Thus, the agricultural sector faces simultaneous imperatives to import less and export more. Which should the sector prioritize?

Benchmarking Nigeria against economic peers

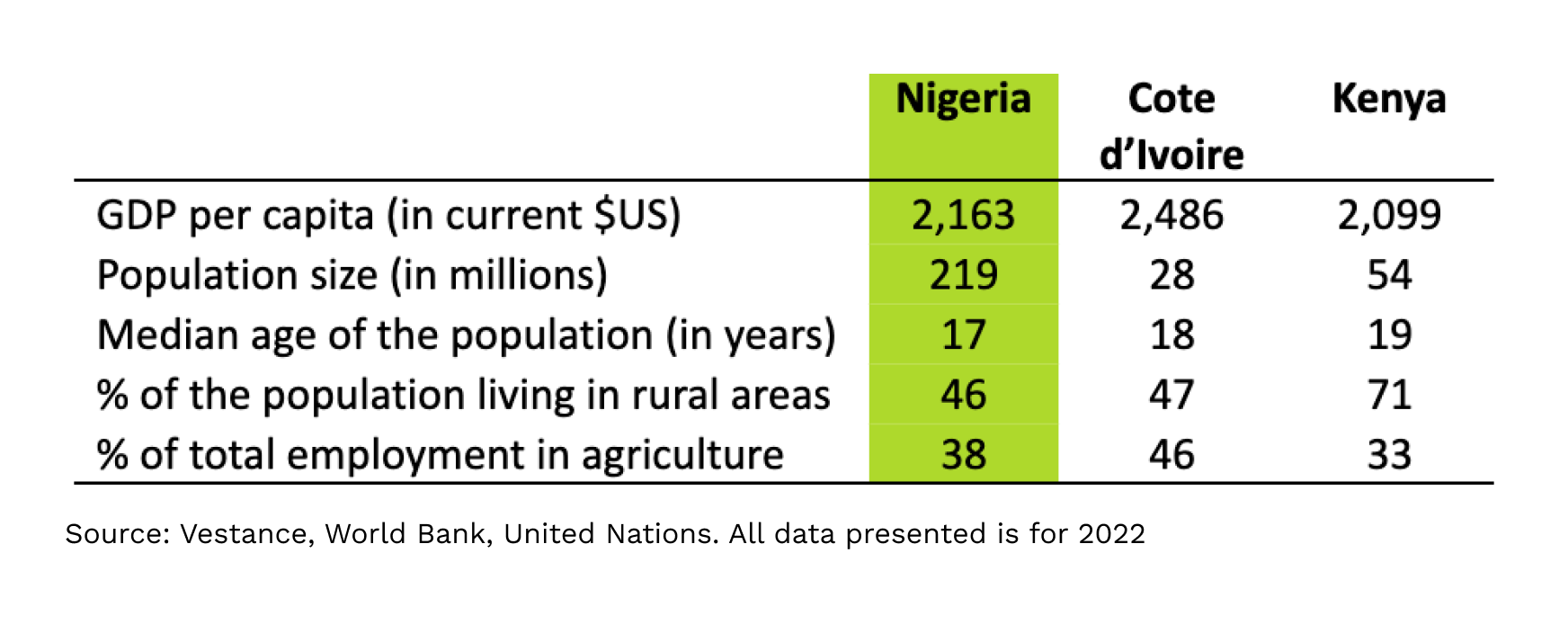

Answering this question requires contextualizing Nigeria’s agricultural trade. One way to do that is to benchmark Nigeria against countries that exhibit similar economic profiles. Four particularly suitable comparators are Kenya, Cote d’Ivoire, Malaysia, and Indonesia. Kenya and Cote d’Ivoire are Nigeria’s regional peers with similar economic and demographic characteristics.

Doppelgangers

Cote d’Ivoire, Kenya and Nigeria have similar socioeconomic profiles.

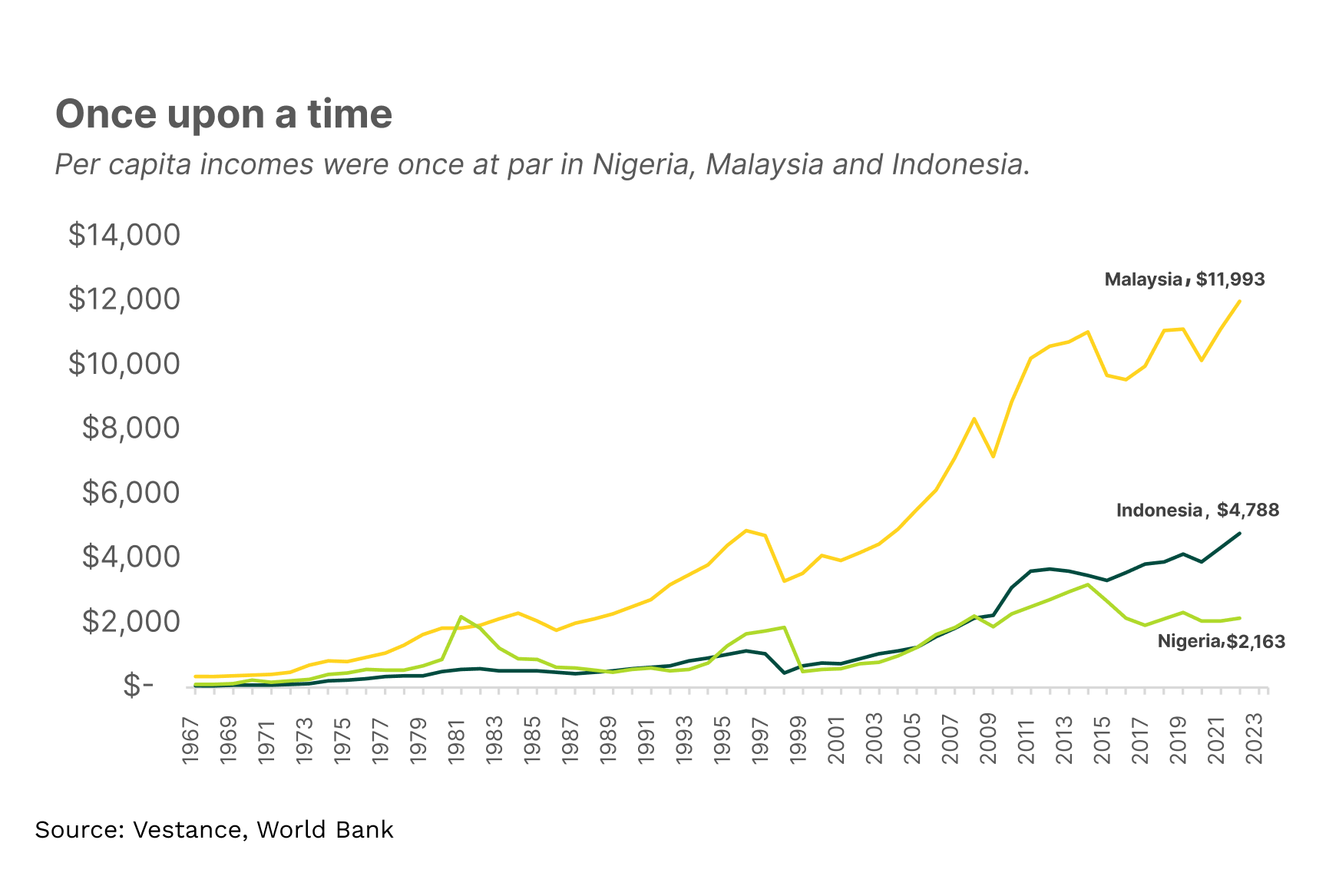

Malaysia and Indonesia are Nigeria’s aspirational peers. Like Nigeria, both countries are oil-rich economies with favourable agro-climatic conditions. Both also had income levels that were once comparable to Nigeria’s but, over the past half-century, have achieved remarkable economic performance that Nigeria can only aspire to today.

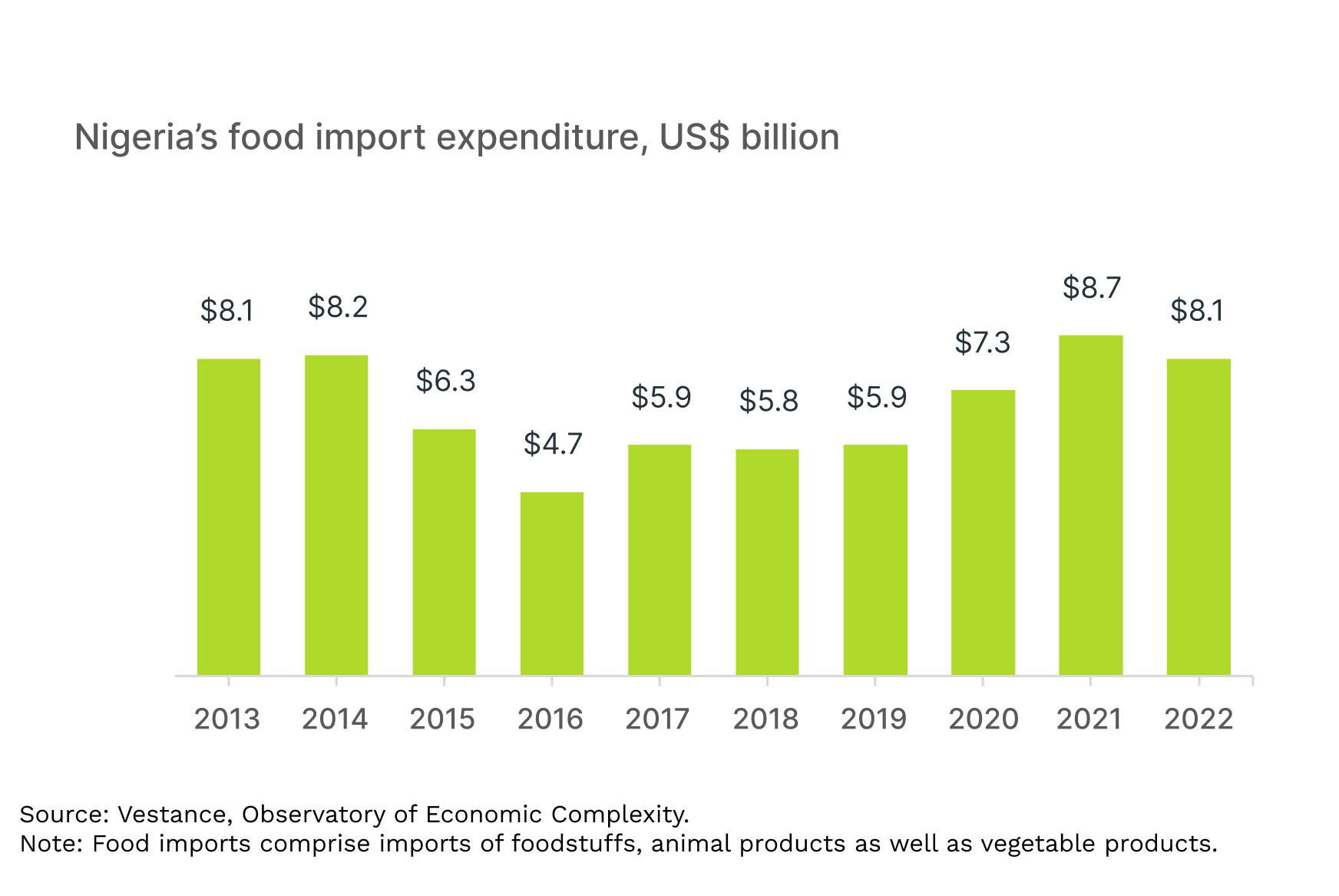

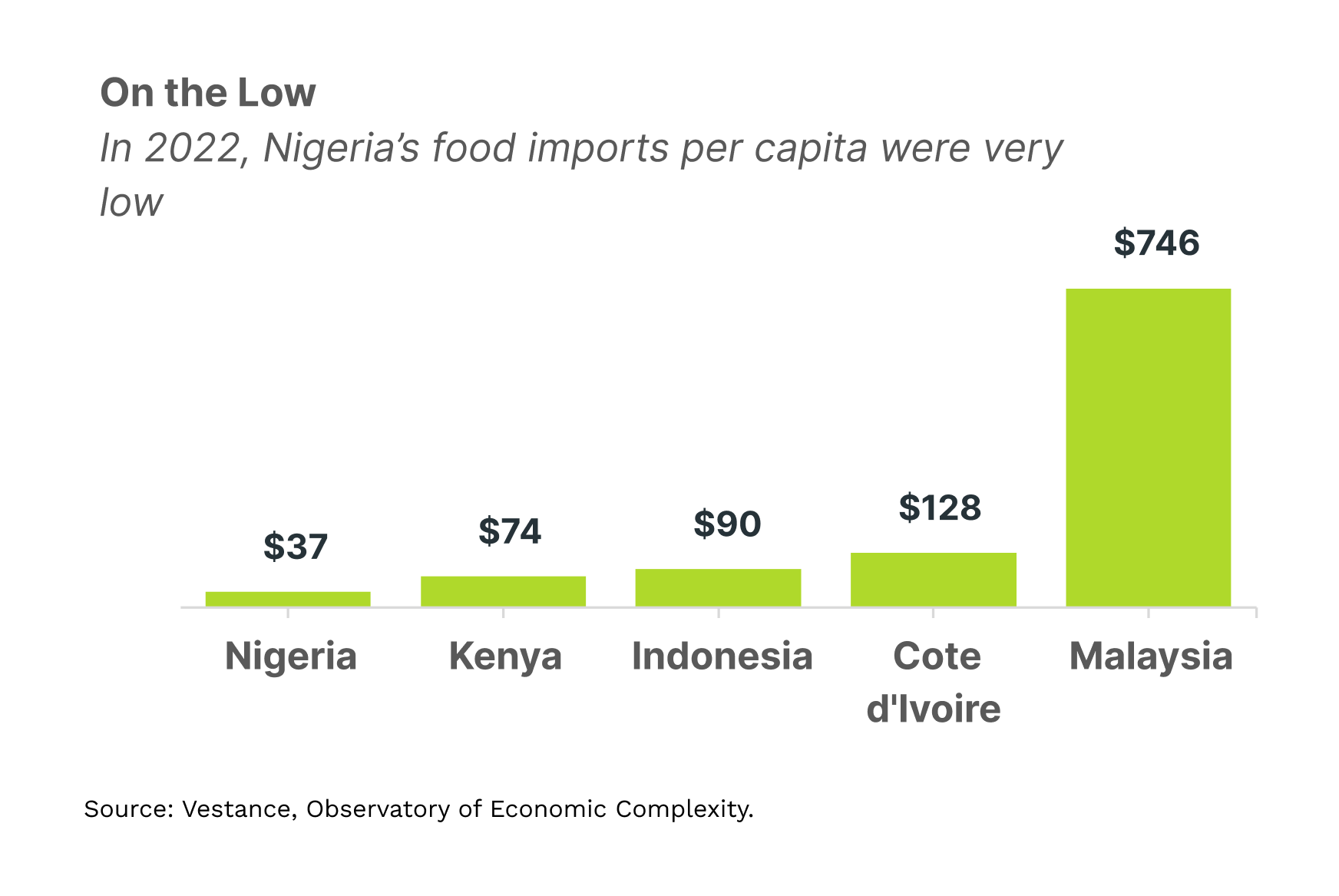

Put into the context of these peers, Nigeria’s food imports are nothing spectacular. In 2022, Nigeria’s total food import expenditure was US$8.1billion. That is about the same as it was a decade before, despite dipping in the intervening years.

Meanwhile, the 2022 food import expenditure of Cote d’Ivoire was $3.6bn and of Kenya $4bn—their combined expenditures almost add up to Nigeria’s ($8.1bn), even though their combined population is less than half of Nigeria’s population. Overall, on a per capita basis, Nigeria imported US$37 worth of food per person in 2022—less than for any of the four benchmark countries.

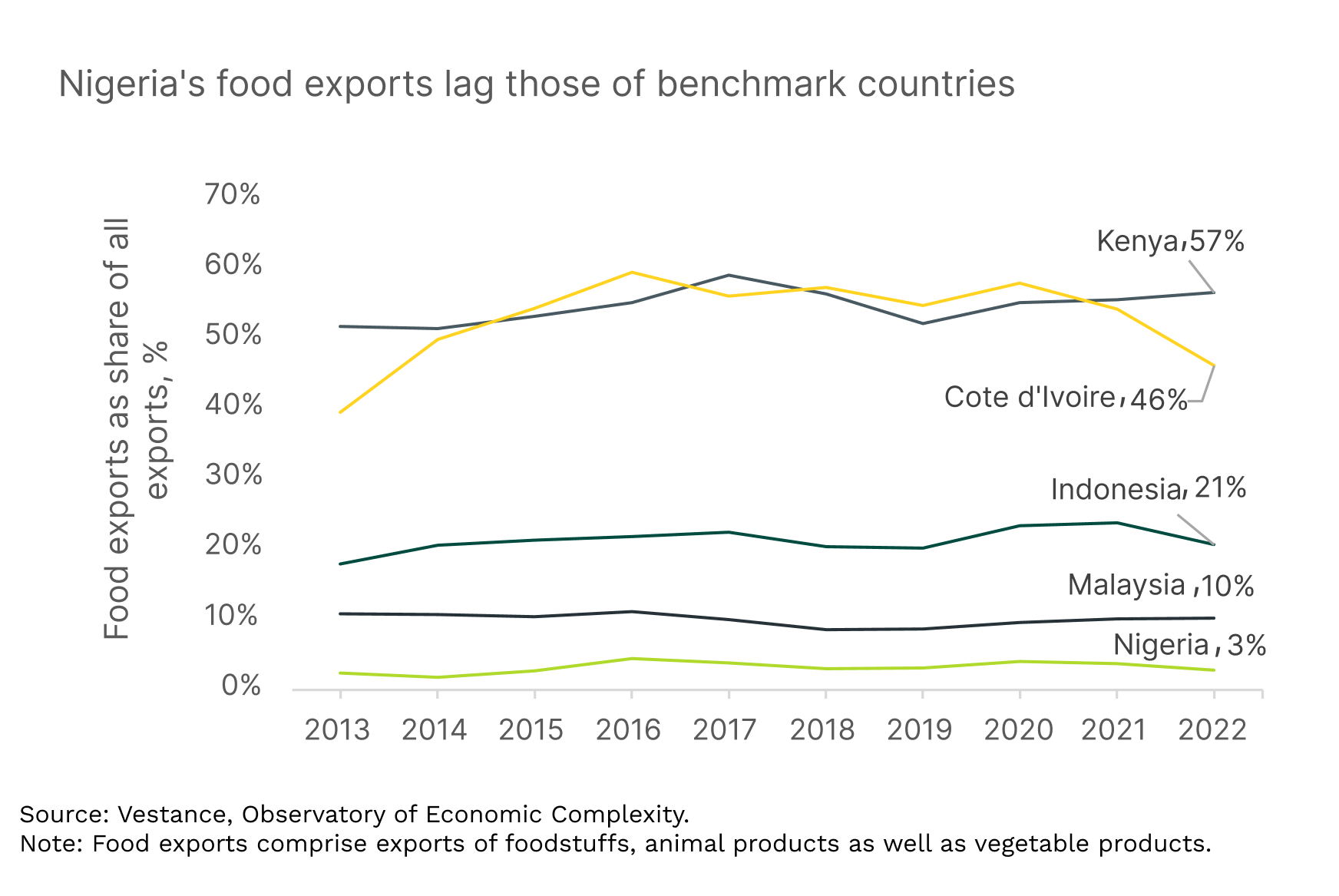

In contrast, agricultural exports are underwhelming. Food exports account for a lower share of total exports in Nigeria than in any of Kenya, Cote d’Ivoire, Indonesia or Malaysia. A policy document of the Agricultural Transformation Agenda — Nigeria’s previous agricultural development strategy — acknowledged that, since the 1970s, Nigeria has lost its dominance in the global trade of agricultural commodities such as groundnut, oil palm, cocoa, and cotton.

Is Nigeria IMPORT-DEPENDENT or EXPORT-SHY?

The real problem, therefore, is that the Nigerian agriculture sector exports too little rather than imports too much. Intuitively, the two issues are intertwined: imports will be unaffordable if exports are negligible.

For this reason, the smart choice would be to prioritize export promotion. Greater agricultural exports can increase Nigeria’s forex earnings, enable the country to pay its food import bills, mitigate macroeconomic vulnerability to oil price slumps, drive productivity growth in agricultural value chains as trade exposes Nigerian farmers to international agronomic best practices, and raise agricultural incomes by enabling farmers tap into global demand.

Above all, export promotion can attract the commercial investments needed to alleviate the country’s food crisis. A key driver to food shortages in Nigeria is that farming is dominated by smallholder farmers, who are fragmented, mostly subsistent and with untapped potential for productivity enhancement. To massively increase the food supply, the agricultural sector needs to attract investors who undertake large-scale, commercial farming using innovative and more productive methods. However commercial investors are motivated by profits, and few investors will invest in Nigerian agriculture if they perceive domestic markets as the sole or main revenue source for their investments. Empowering Nigerian agriculture to integrate into global value chains will make the sector more appealing to much-needed commercial capital.

Stay up-to-date!

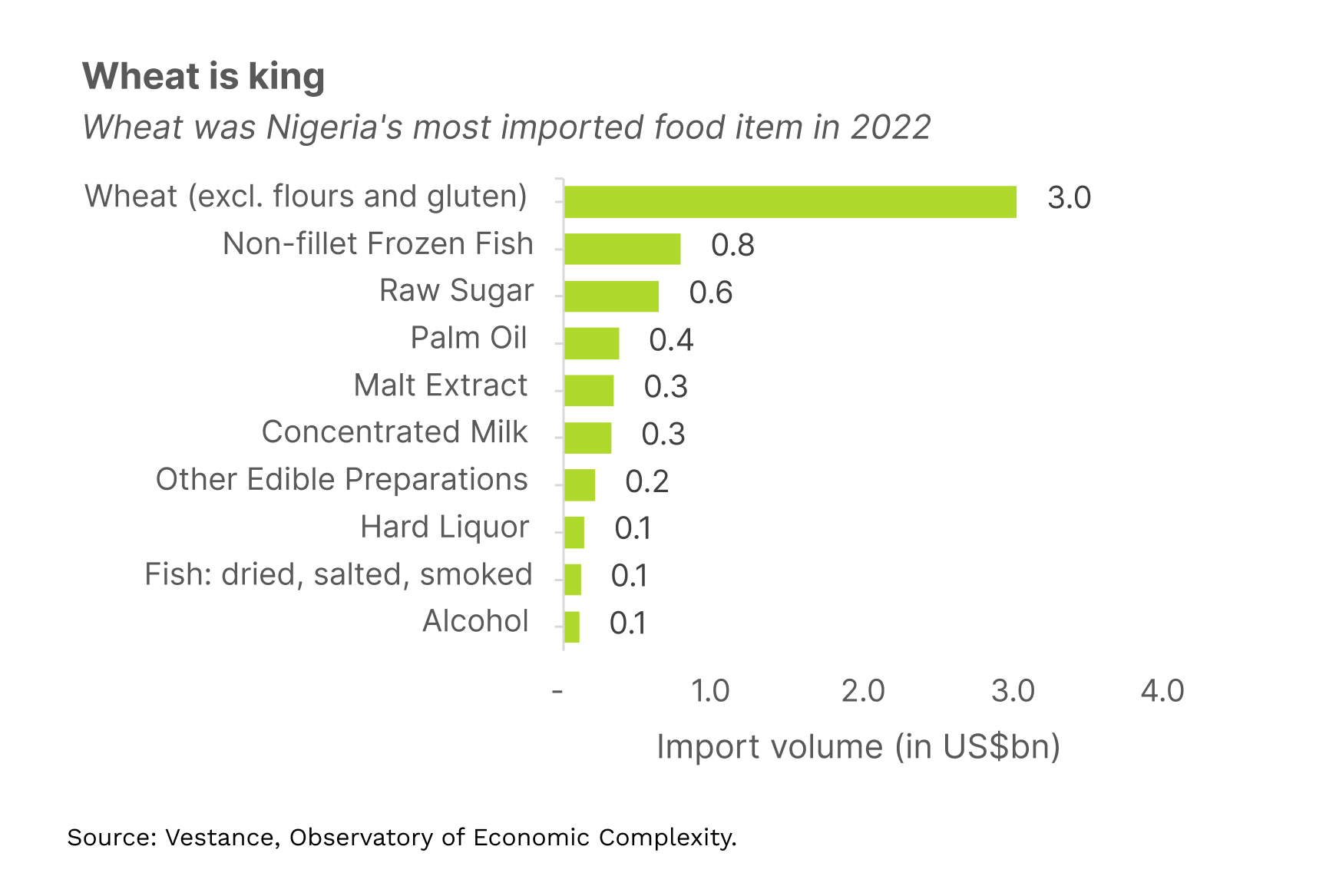

To be fair, import substitution is not without its merits. For instance, in an increasingly geopolitically fragmented world, reducing food imports does have national security appeals—but only if implemented successfully. Unfortunately, the prospects of achieving significant progress with food import substitution in Nigeria are bleak. For one, Nigeria’s most imported food item is wheat—a crop with unproven agronomic viability in tropical climates like Nigeria’s. Past efforts to redirect consumer preferences towards locally-grown substitutes, exemplified by the cassava bread and the #BuyNaijaToGrowTheNaira initiatives, have suffered quick demises.

The way forward

To capture larger shares of international markets, Nigerian agribusinesses must out-compete those from rival countries, through cost leadership and value addition. For that to happen, key constraints to agricultural exports in Nigeria will need to be addressed.

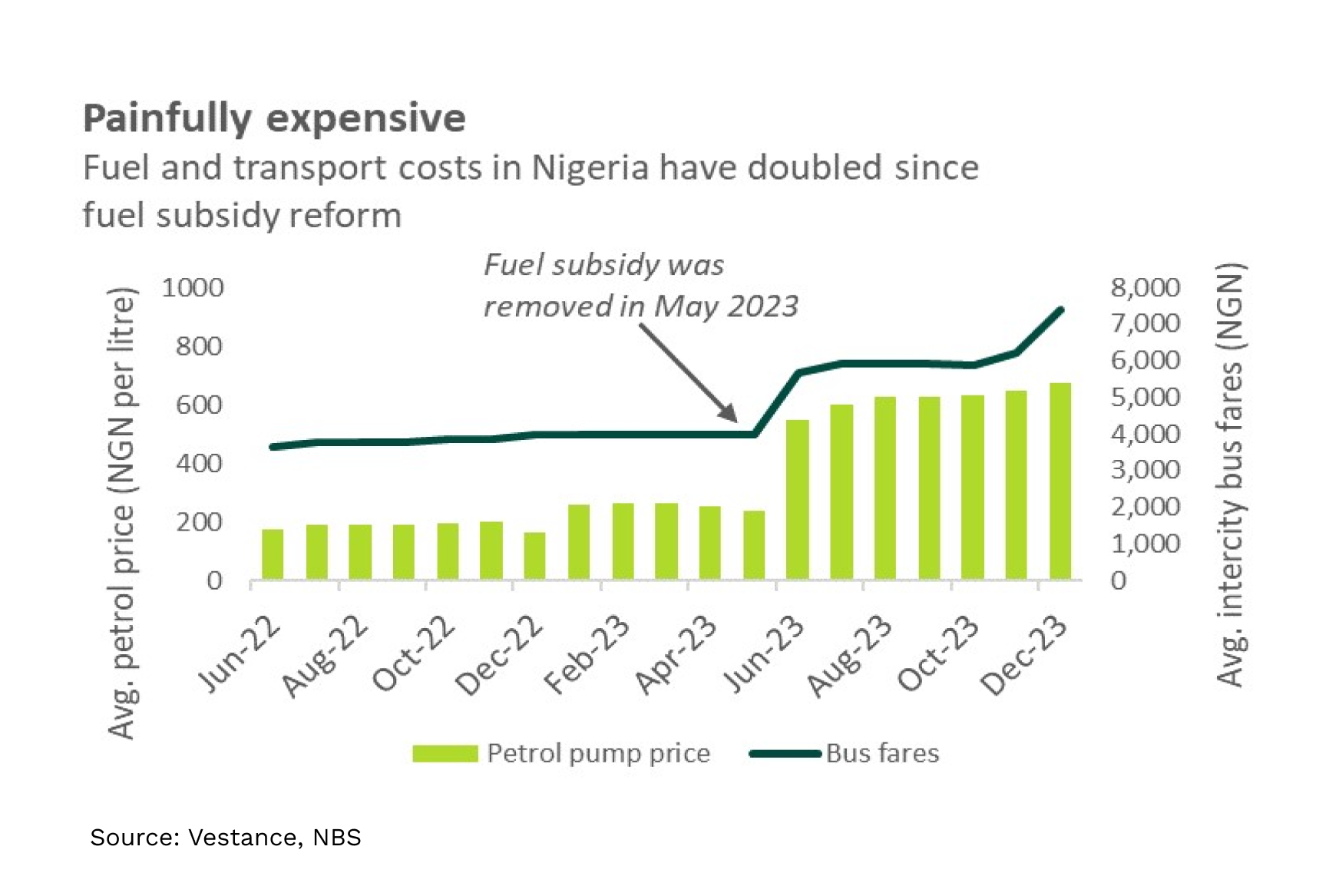

The first is infrastructural bottlenecks, particularly concerning energy and transport. Farming operations, ranging from input supply to produce disposal, require reliable and affordable energy and transport services. However, following recent fuel subsidy reforms, increases in energy and transport costs have made these farming operations—and by extension, food prices—painfully expensive. This is an economy-wide problem but, to be able to compete internationally, agribusinesses cannot wait around for economy-wide solutions. One alternative option to power farming operations is off-grid renewable energy solutions, which are gaining popularity in Nigeria. Ongoing improvements in Nigeria’s rail networks also open up rail transport as an alternative to road transport for agricultural logistics. To nudge agricultural operations in these directions, policymakers in the agricultural sector should explore the viability of these options for various agricultural value chains. Wherever viable, policymakers should provide the support required for adoption—for example, financial support to offset the high upfront costs of renewable energy.

Another barrier is legislation. Agricultural exports are subject to the Export Prohibition Act, an active piece of legislation that forbids the exports of raw and derivative forms of agricultural commodities such as beans, cassava, maize, yam and rice. This law, originally made in 1989 and amended in 1999, needs revision, as these are commodities that Nigeria has the potential to produce abundantly and inexpensively. Continued prohibition of their exports would be a missed opportunity to harness global market opportunities.

Policymakers should foster the digitalization of agricultural commodity markets. The market channels for many commodities rely on middlemen who collect the raw produce in small quantities from fragmented smallholder farmers and perform quality enhancements (such as sorting, cleaning, and drying), before selling in aggregated volumes and at marked-up prices to the final exporters or processors. While middlemen play a critical role in connecting farmers to exporters, they can increase exporters’ transaction costs and time. Additionally, malpractices by middlemen and weak contract enforcement also expose farmers and exporters to increased financial risk. Digitalizing commodity markets can help reduce these barriers, by allowing exporters to interact directly with farmers on price, quantity and quality specifications, as well as logistic arrangements.

Finally, government support for export-oriented agribusinesses is crucial. Let’s be honest, global agricultural trade is no fair competition. Some countries have superior market power in international food markets. Some provide subsidies that help their farmers dominate the global agricultural trade. To be competitive, Nigerian policymakers must stay abreast of international agro-commodity trade trends and, whenever needed, provide targeted incentives (such as tax breaks, export credits, and subsidies) that help the country’s agribusinesses level the playing field.

Our Advice

When the Nigerian government looks at the agricultural sector, it sees a sector that imports too much. What it should see instead is a sector that exports too little. For the good of Nigerian agriculture and economy, the government’s priorities in the sector must change.

References

- Benoit, D., & Mathilde, D. (2014). Major Players of the International Food Trade and the World Food Security. Agriculture et géopolitique

- Central Bank of Nigeria. (2023). What You Need to Know about CBN’S Lifting of FOREX Restrictions

- Federal Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development. (2022). National Agricultural Technology and Innovation Policy

- Joshua, A. (2011). Market Power in Nigerian Domestic Cocoa Supply Chains. ResearchGate.

- National Bureau of Statistics. (2022). National Agricultural Sample Census (NASC) Report 2022. NBS.

- Oxfam. (2002). Stop the Dumping! How EU Agricultural Subsidies Are Damaging Livelihoods in the Developing World. Oxfam Briefing Paper.

- Shekhar, A., Jiaqian, C., Christian, E., Roberto, G.-S., Tryggvi, G., Anna, I., . . . Juan, P. T. (2023). Geoeconomic Fragmentation and the Future of Multilateralism. International Monetary Fund.

- Todd, B., Mulubrhan, A., & Adebayo, I. O. (2020). The Relative Commercial Orientation of Smallholder Farmers in Nigeria. International Food Policy Research Institute.