Pricing Was Only the Beginning

In an earlier article, we examined how Nigeria’s beef sector is constrained by a pricing model that does not reflect differences in quality. We argued that without transparent and reliable pricing, farmers, consumers, and investors are left navigating a system that feels more like a guessing game than a market. But pricing is just one piece of a much larger puzzle.

The livestock industry is built on many interconnected parts. Grass and grains feed the animals, veterinary services keep them healthy and financial returns attract investors. To unlock the sector’s potential, Nigeria must begin to view livestock production as part of an integrated value chain. This article expands the conversation by highlighting how feed can become the foundation for a stronger and more profitable industry.

Challenges and lessons from global and local systems

Feed is the largest cost and productivity constraint in Nigeria’s livestock systems, accounting for about 70 percent of production cost in intensive systems. For poultry and pigs the figure often rises higher, while for small and large ruminants, especially when dependent on open grazing, the cost is lower. Many herders still depend on open grazing. During the dry season, when pastures wither, animals lose weight and market value reduces. This irregularity of natural forage means seasonal shortages and inconsistent returns for producers, discouraging investment.

Commercial feedlot systems, although still in their early stages of adoption in Nigeria, show what structured feeding can deliver. The Lagos Feedlot Program under the Red Meat Initiative has reported an average cattle weight of 450 to 500 kilograms compared with 300 kilograms in open grazing systems. This difference translates into better carcass yield, improved traceability, and higher revenue.

Globally, feed is the foundation of livestock profitability. In Brazil, cattle production relies on intensified pastures, which are open grazing systems that are actively improved and managed rather than left to grow naturally, combined with feedlot finishing to maintain stable performance. During the dry season, cattle are confined for 80 to 120 days and can gain up to 120 kilograms in a predictable and consistent way. In contrast, Nigeria still depends on open grazing with low-quality natural grasses and very limited investment in managed fodder, which limits productivity.

Nigerian farmers already rely on a wide variety of indigenous plants for small ruminant feeding. A study identified 52 species used by households while another documented more than 160 species used for goat and sheep feeding. Some plants were identified by farmers as highly preferred, showing the depth of local knowledge.

Despite this diversity, the number of legumes identified in these surveys is very low. This leaves a major gap because legumes are critical for protein supply in feed and for improving soil fertility when integrated into forage systems. If structured properly, such systems could reduce dependence on open grazing, improve nutrition, and raise productivity.

The Market Landscape

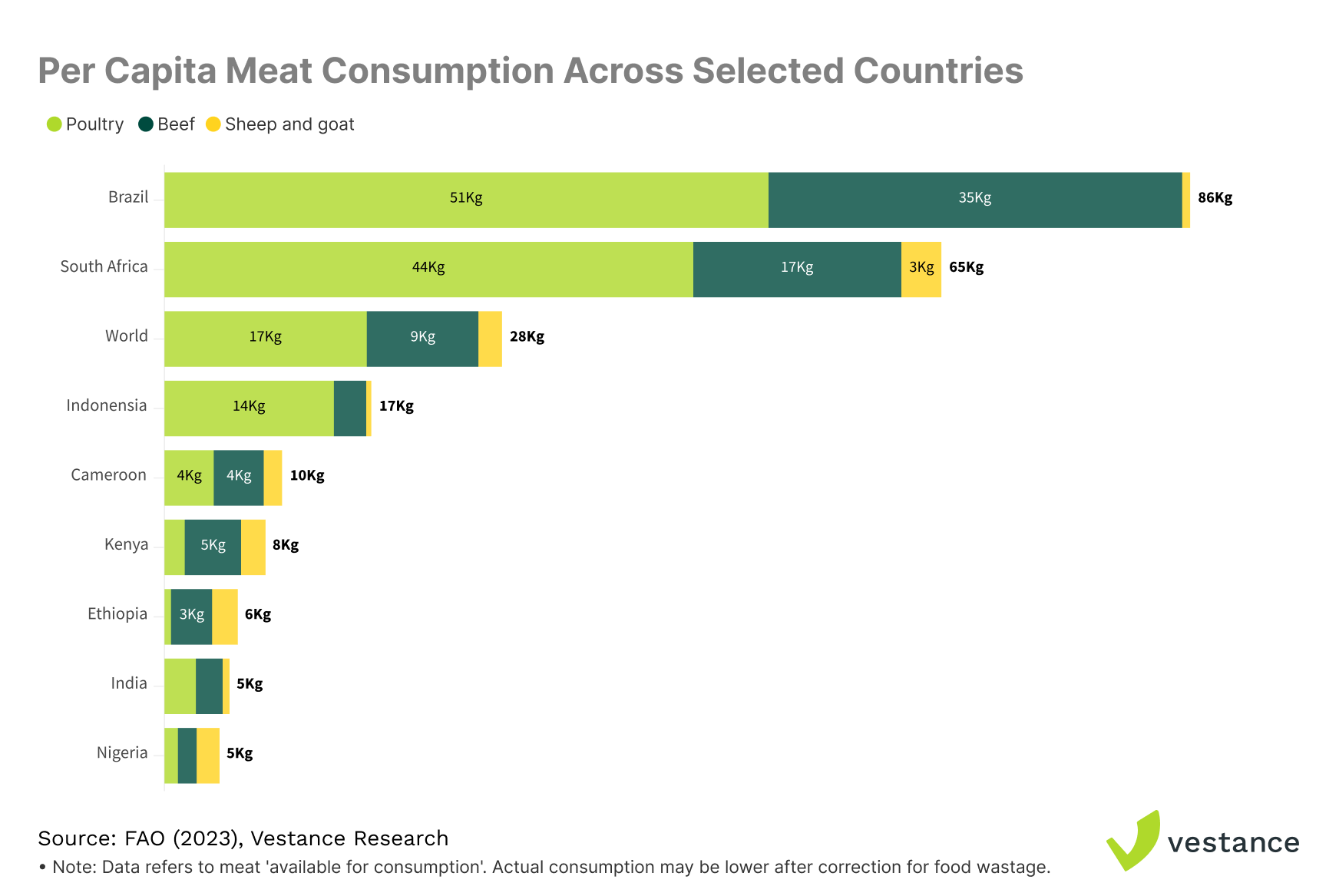

Nigeria’s per capita consumption of animal protein is about 45 grams, below the FAO recommendation of 54 grams. The country’s livestock population is large, with about 34.5 million goats, 22.1 million sheep, and 13.9 million cattle, yet it is still not enough to meet national demand. Low feed quality and inefficient production systems continue to limit output and increase costs. This makes meat and milk more expensive and less accessible to many households.

To address this, the Central Bank of Nigeria-owned NIRSAL Plc launched a Feedlot Management Training Programme to strengthen the capacity of value chain actors. This initiative aligns with the recent 2.5 billion dollar foreign direct investment by JBS, the world’s largest meat processor. The deal signals both the potential of Nigeria’s livestock sector and the role of feed in driving growth and closing the protein deficit.

Several companies are already active, particularly in the poultry feed industry. Premier Feed Mills, a subsidiary of Flour Mills of Nigeria Plc, is one of the largest producers and the biggest aqua feed manufacturer in Sub-Saharan Africa. Livestock Feeds Plc, part of UAC of Nigeria Plc, manufactures and distributes poultry and livestock feeds. Amo Byng Nigeria Ltd focuses on poultry, aquaculture, and livestock feed. Grand Cereals produces poultry and fish feeds under brands such as Grand and Vital. Other players include Chikum Feed, Novum Agric Industries, and Lizasteph Nigeria Limited. These firms show that structured feed production is viable, but most efforts remain concentrated in poultry. Ruminant feed is still a wide open space.

The Opportunity

The challenges of livestock feed in Nigeria, particularly in cattle production, point to clear business opportunities. Pasture intensification with improved grasses such as Brachiaria (Palisade grass) can raise yields and support rotational grazing. Silage and hay preservation can smooth the supply in feed-scarce months. Hydroponic fodder systems in peri-urban areas can provide a steady supply of green feed where land is limited. Feedlot finishing, already piloted by the Lagos government, shows how predictable weight gain and better carcass quality are achievable locally.

Forage should not be treated as an afterthought but as the seed of value creation. Entrepreneurs who invest in feed systems from pasture development to feedlot finishing can stabilise production and capture rising consumer demand. What hinders today is the same space where tomorrow’s value will be built.

Brazil is a leading example. Over the past two decades, it has built a strong feed market around beef by combining improved pastures with feedlot finishing. Grasses like Brachiaria and Panicum now support higher yields and predictable weight gain. About 15 to 20 percent of cattle are finished in feedlots, improving carcass quality and export value. Ethiopia shows similar progress in Africa. Guided by its Livestock Master Plan, it has promoted forage seed multiplication and private feedlot investment for domestic and export markets. Around Addis Ababa and Adama, several feed firms produce formulated rations for small and medium-scale feedlots.

Just as the poultry feed industry has attracted organised investment and scaled rapidly, ruminant feeding could become the next sweet spot for agribusiness. Opportunity lies in developing grass-legume mixtures and adapting the already identified plants through indigenous knowledge for large ruminants. Leveraging indigenous plant diversity, strengthening legume introduction, and adapting fodder systems to cattle could unlock value in the ruminant feed system. However, investors must contextualise planning and execution to match their strengths and weaknesses.

Conclusion

Nigeria’s livestock sector cannot grow on grazing alone. The future lies in managed forage, silage, feedlots, and structured feed production that serve both poultry and ruminants. Feed is not simply a cost item. It is the foundation of productivity, the basis for meat quality, and the most investable opportunity in the sector. Investors who move early can capture value in a market that is not only undersupplied but also essential to the country’s food security.

Stay up-to-date!

About Vestance

At Vestance, we provide clear, data-driven insights and advisory to help investors make smart decisions in the agricultural space. Using both past and current market data, Vestance helps stakeholders in the agri-food supply chain to act based on reliable market trends and information. Talk to us for your venture need.